Neurology in Germany II – Successful years before 1933

Neurology in Germany II – Successful years before 1933

by Helmuth Steinmetz

Following last month’s chapter 1 about “founding fathers of the 19th century” we here continue this historical retrospect with a short review of German neurology in the early 20th century. Again, we do so by focusing on some of the most influential persons of that time. All of them have in common that they utilised emerging new methods providing unimagined insights into brain structure and dysfunction. In fact, their discoveries fall into a truly “golden age” of neurology in Germany [1, 2].

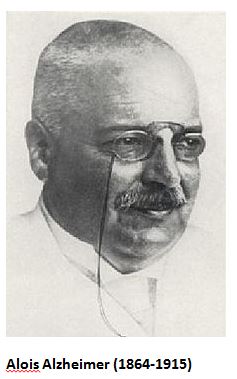

Alois Alzheimer and histopathology

Born in 1864, Alois Alzheimer was among the first to use microscopy of stained postmortem brain slices for the study of neuropsychiatric conditions. Together with Franz Nissl, he histologically characterized progressive paralysis, arteriosclerotic brain damage and, in 1906, another “peculiar affection of the cortex” later named after him by Emil Kraepelin. Alzheimer was confident that tissue characterisation, but not functional localisation, would prove to be the key to a better understanding of brain disorders. To him belongs much of the merit of having unraveled the organic nature of the dementing conditions and to distinguish between them. It should be kept in mind that today’s clinical classifications followed the histopathological ones, not vice versa.

Born in 1864, Alois Alzheimer was among the first to use microscopy of stained postmortem brain slices for the study of neuropsychiatric conditions. Together with Franz Nissl, he histologically characterized progressive paralysis, arteriosclerotic brain damage and, in 1906, another “peculiar affection of the cortex” later named after him by Emil Kraepelin. Alzheimer was confident that tissue characterisation, but not functional localisation, would prove to be the key to a better understanding of brain disorders. To him belongs much of the merit of having unraveled the organic nature of the dementing conditions and to distinguish between them. It should be kept in mind that today’s clinical classifications followed the histopathological ones, not vice versa.

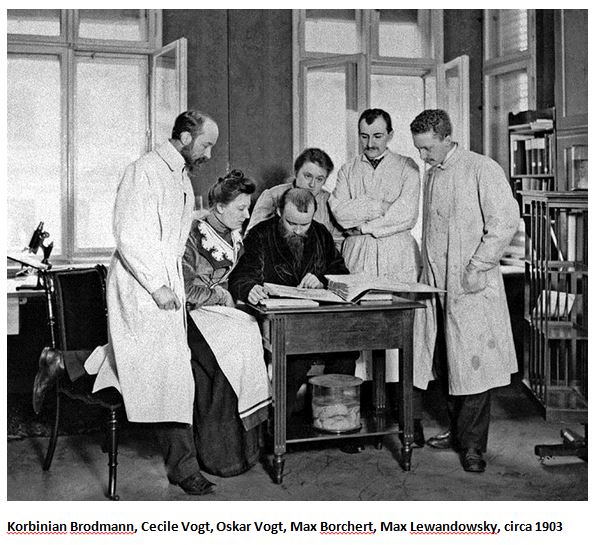

Cecile and Oskar Vogt, Korbinian Brodmann and brain architecture

It was 1898 in the laboratory of Pierre Marie in Paris where the 28 year-old Oskar Vogt met his later wife Cecile Mugnier, one of the first female neurologists in history. Back in Berlin, joined by Korbinian Brodmann, they started to use serial whole-brain sections to microscopically delineate cortical areas, thalamic and striatal nuclei and their fibre connections (“cyto- and myeloarchitectonics”). Complementing these anatomic studies with electrical stimulation of cortical fields (in apes) the Vogts showed that structural borders coincide with physiological ones and vice versa, a finding simultaneously confirmed for the human cortex by their contemporary Otfried Foerster during the 1920ies in Breslau (Wroclaw). The Vogts assumed that their concept of structural-functional “topistic units” might also explain patterns of damage in genetic, toxic or metabolic disorders, something one might refer to as “selective vulnerability” today.

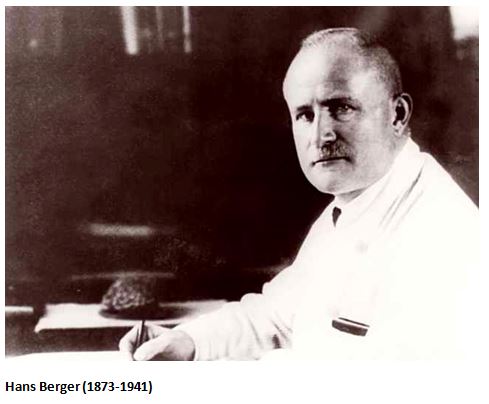

Hans Berger and the electroencephalogram

“Indeed, I believe to have found the electroencephalogram of man and hereby publish this for the first time” were the famous words written by 56 year-old Hans Berger in 1929, 5 years after his original recording. Having entered the Psychiatry Clinic in Jena 1897, at that time led by Otto Binswanger, Berger’s goal had always been the objective measurement of “psychic energy”. First studies in cats and dogs were followed by direct recordings from the human brain surface during open surgery, and in 1924 from the scalp. Partly due to Berger’s secluded scientific lifestyle, it was not before 1934 that the English physiologist Edgar Adrain recognised the importance of his observations, also lending the name “Berger rhythm” to what Berger had described.

“Indeed, I believe to have found the electroencephalogram of man and hereby publish this for the first time” were the famous words written by 56 year-old Hans Berger in 1929, 5 years after his original recording. Having entered the Psychiatry Clinic in Jena 1897, at that time led by Otto Binswanger, Berger’s goal had always been the objective measurement of “psychic energy”. First studies in cats and dogs were followed by direct recordings from the human brain surface during open surgery, and in 1924 from the scalp. Partly due to Berger’s secluded scientific lifestyle, it was not before 1934 that the English physiologist Edgar Adrain recognised the importance of his observations, also lending the name “Berger rhythm” to what Berger had described.

Neurology and World War I

Tragically, the importance and autonomy of neurology in Europe was strengthened considerably during and after the Great War 1914-1918. This was particularly so in Germany where neurology had remained integrated in psychiatric institutions in most universities and hospitals since the 19th century. The main reason for this unforeseen “consolidation” was the large number of patients surviving shots to the head acquired in the trench. Specialised institutions were opened (“Hirnverletztenheime”) allowing better care but also detailed examination of patients suffering from the sequelae of focal injury of the nervous system. One of the best-known German compilations of neurological knowledge so obtained is probably Karl Kleist’s map of the localization of cortical functions published in 1934 [3].

Literature

1. Kolle K (Ed). Große Nervenärzte, Bd 1-3, Thieme 1956, 1959, 1970.

2. Kömpf D (Ed). 1907-2007. 100 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie, Berlin, 2007.

3. Kleist K in Handbuch der der Ärztlichen Erfahrungen im Weltkriege 1914/1918 (Bonhoeffer, K, Ed.). Barth, Leipzig, 1934.

Professor Helmuth Steinmetz works at the Center of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University Hospital/ Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany