The EAN Student Task Force is pleased to present the winners of this year’s ‘Why Neurology?’ essay competition.

The aims of the competition are to understand the incentives of choosing neurology as a subspecialty and to get to know EAN Student members better, whilst also making neurology more visible among undergraduate medical students. Recruiting young and driven future neurologists who may later become leaders and mentors in neurology is a high priority for the EAN, as is increasing the engagement of medical students in EAN activities.

To capture the ideas expressed by the future neurologists and to provide an exciting opportunity for undergraduate students, the winners of the ‘Why Neurology?’ essay competition have been invited to present their work at the congress, onsite in Helsinki, on Sunday, 30 June, between 14:00 – 14:30 (EEST) in the Scientific Theatre (see this session in the EAN 2024 programme planner).

We are proud to present the five winning essays below. Congratulations to the authors!

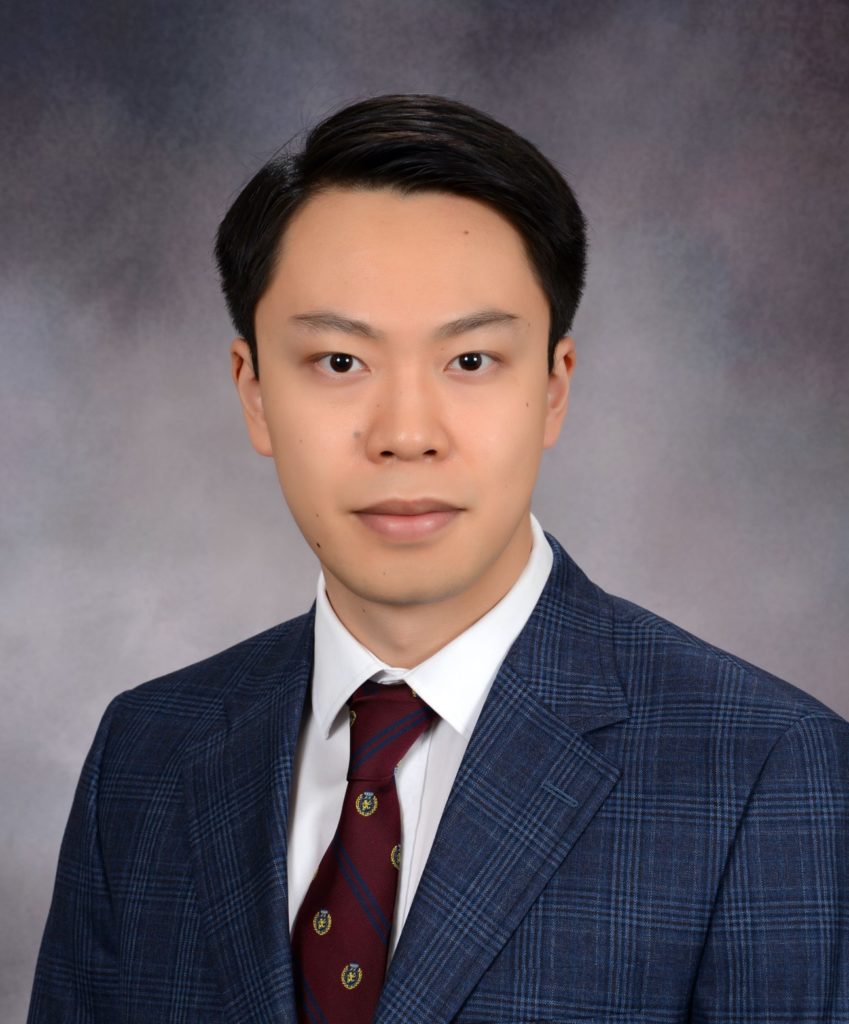

Yuki Kawamura, UK, 4th year Student

“It might not kill you, but it still kills a part of you,” Rudy* said pensively, “you’re never the same, really.” Rudy, a member of a stroke survivor’s group where I volunteer, appeared to have recovered well after stroke from a medical perspective. Yet, the faltering tone in his voice told me that it wasn’t his residual gait problems that he was alluding to. I found myself pondering, what does it mean to save someone?

Perhaps too naïvely, in my childhood I always believed that with enough effort and good luck, I could discover a miracle drug that would eradicate stroke and that nobody should die of a stroke thereafter. Indeed, saving lives is paramount. But is it all we need to save?

The man who yearned to have the independence to wash himself in the shower and regain his dignity; the lady who was now easily brought to tears but insisted she was never like so before her stroke; the man lamenting how his stroke was “invisible” so none of his co-workers could fathom that his illness robbed him of his attention span – stroke might not have taken their lives, but certainly a part of each one of them.

As a medical student, I have had the fortune and privilege of being involved in patient care, but my most meaningful experience in neurology was with a lady with whom I interacted not as a medical student, but as a stroke group volunteer. The lady, Tatiana*, had lost most of her English after her stroke. The first time Tatiana came to our meeting, she sat in her chair looking down at her toes, avoiding eye contact. A few members tried to speak to her, but seeing that she did not engage much, they went back to their own conversations. However, I was surprised to hear her son describing her as a cheerful and independent lady – a stark contrast to how she appeared that day. I realised that she was perhaps silent not because she disliked conversation, but rather because she found it challenging to keep up with others. Seeing that she had often faltered when trying to express herself, I tried to engage with her by asking her very simple questions with the help of a translation app and giving her ample time. Although she initially only gave an occasional nod, I tried to be empathetic and pick up nonverbal cues to see if she wanted a break, or whether she seemed to be interested in the topic. Occasionally, I just sat quietly next to her so she would not feel compelled to reply to any of my questions but would still be able to make conversation if she so wished. Our first meeting was marked by sporadic and punctuated conversation, and it remained so for the next few weeks. Yet, when I arrived halfway through a meeting several months later, I saw her look up at me and smile for the first time since I had met her, and to my surprise, she was engaged in a conversation with the person next to her. Although I was not involved in her medical care, I felt that I played a small part in her recovery and that this was perhaps my first success as a budding neurologist.

I was attracted to neurology by how it simultaneously utilises cutting-edge technology yet is perhaps one of the specialties which most values a traditional clinical approach. I enjoy clinical reasoning by taking a thorough history and performing a detailed examination to localise a lesion and perhaps even uncover subtle defects not immediately obvious on imaging. Importantly, my experience with Tatiana taught me that we learn so much – and perhaps treat a little – by listening.

My goal as a neurologist is to improve clinical care to minimise disability and neurological deficits in stroke patients. As a clinician, I wish to pursue this goal by carefully listening to the patient to recognise and treat even subtle deficits which may affect a patient’s quality of life. I have also pursued my goal through research, where I analyse samples collected from stroke patients to identify inflammatory changes which might be responsible for neurological deficits, with the goal of developing drugs to modulate deleterious immune responses.

Patients have taught me it can often be small, spontaneous moments of joy in a seemingly ordinary day that they most hold dear; it is these moments, now, which I strive to save.

*All names are pseudonymised for anonymity.

Raquel Monteiro, Brazil, 5th year Student

I’m an engineer. You’re probably wondering: “What’s an engineer doing here?” Well, let me share a story that not only connects me to the field of neurology but also marks a journey driven by love, loss, and a quest for purpose—a journey inspired by my brother, Daniel.

It all began before I was even born. Daniel was adopted into our family as a newborn. More than just a sibling, he was a shining light living with a serious condition that shadowed his life. He had neurological sequelae due to congenital toxoplasmosis, leading to intellectual disabilities. Despite the challenges, his beautiful soul never ceased to inspire everyone around him. He was special in every single way.

Back when I was a little kid, I’d pray for a miracle to have my brother cured, only to find out later that such a cure was unachievable. His brain damage was permanent, requiring extensive medical care.

Daniel passed away a few years ago, and it was a profound loss. That tough period made me reevaluate my life’s direction. As an engineer, I’d spent years solving problems and envisioning the future through technology. Yet, after I lost my brother, I started questioning my life’s purpose. A deep question haunted me: was I truly making a difference? I felt that just working and paying bills wasn’t enough anymore. I had to do something to make the world a better place, especially for people like my Daniel. In this search for meaning, I realized that to honour Daniel’s memory and to impact lives in a significant way, I needed to pivot my journey toward neurology.

It was one of the hardest decisions I have ever had to make. Transitioning from a stable career to the demanding path of medical school, especially in my late twenties, felt intimidating. However, the pull toward neurology was undeniable, and it wasn’t simply a matter of finding a new occupation; it was about answering a calling I couldn’t ignore. My passion for the field, my desire to explore the complexities of the brain, and my hope to prevent neurological conditions became the only way forward.

My engineering background is the foundation of my unique approach to neurology. I’m deeply interested in the potential of technology to transform neurological care. The same principles that guided me as an engineer—to innovate, to optimise, to push the boundaries of what’s possible—are what drive me to explore how technology can revolutionise brain health.

The convergence of technology and neurology opens up unprecedented possibilities, from wearables that monitor neurological health in real-time to AI-powered diagnostic tools that can predict and prevent conditions before they occur. I see a future where advances make brain health monitoring and disease prevention part of everyday life. I want to be at the forefront of this integration, making care accessible to everyone, everywhere.

I daydream about a future where neurology isn’t just reactive but proactive, where brain health is prioritised and maintained from an early age, and where technology bridges the gap between what is and what could be. My goal is to blend my engineering skills with neurology to create solutions that don’t just minimise the effects of brain disorders but prevent them altogether. If we can do that, stories like Daniel’s might inspire real change and innovation.

This transition goes beyond career change. It symbolises my pursuit of purpose and my dedication to making a tangible impact on others’ wellbeing. It’s a tribute to Daniel’s memory and a commitment to shaping a future where brain health is accessible, preventative, and enriched by technology. It’s a significant shift from my initial path, but I truly believe that this is the right direction to head in, where I can make a truly impactful difference.

So here I stand—an engineer and soon-to-be medical doctor entering the world of neurology. My journey is motivated by love, shaped by loss, and driven by the belief that with the appropriate tools and knowledge, we can significantly improve lives. Every step is fueled by a deep-seated purpose: to prevent what can be avoided, to heal what can be healed, and to explore every avenue that technology opens—all while being driven by a profound passion for service and care. Daniel taught me the importance of resilience, hope, and the power of a compassionate heart. As I move forward, these lessons serve as my guiding force, reminding me that it is often during our most challenging times that we find doors to new beginnings.

Yuqing (Clara) Chen, UK, 4th year Student

Using my Brain to Understand the Brain: ‘Meta-Neurology’

I’ve always enjoyed using my brain, whether for a sudoku or learning a new language. Now as a medical student, what better way to use my brain than to use it to understand itself? I’ve named this ‘meta-neurology’; I’ll now explore how I think neurologists utilise each lobe of their own brains in their clinical practice.

Frontal Lobe:

The frontal lobe governs executive functioning, including decision-making and problem-solving, and this directly mirrors the cognitive processes required for the neurologist to efficiently extract and synthesise clinical data, such as formulating differential diagnoses, interpreting diagnostic testing, and generating management plans. Important too is its governance of personality and emotion, to establish the patient-clinician rapport for effective communication and empathy.

Parietal Lobe:

The parietal lobe integrates sensory and spatial input, which neurologists rely on for a thorough and comprehensive neurological examination. Whether evaluating visuospatial abilities, eliciting reflexes, or assessing tactile discrimination, neurologists leverage their own sensory modalities to delineate abnormalities and localise lesions.

Temporal Lobe:

The temporal lobe is for memory encoding and auditory processing, and hence facilitates diagnosis as well as clinical communication, to allow detailed medical histories and interpretation of speech. Its role in working memory and attention contributes to the neurologist’s capacity for the synthesis of large volumes of information, for retrieval and retention.

Occipital Lobe:

Finally, the occipital lobe has a role in visual perception and interpretation, important for the neurologist to evaluate inspection of clinical signs of neurological deficit as well as interpreting neuroimaging. More abstractly, its role in visualisation allows the construction of mental representations of anatomical structures and pathological processes, enhancing diagnostic judgement.

As a neurologist, the brain serves as the instrument and the vessel from which neurological disorders can be explored and managed. Each lobe contributes uniquely to the neurologist’s cognitive armamentarium, enabling the evaluation and management of complex neurological disorders. ‘Meta-neurology’ highlights this symbiotic relationship – I am inspired to pursue neurology, using my own brain to understand the complexities of the patient’s brain.

Mara Verginer, Austria/Italy, 5th year Student

It is one of my favourite jokes, even though I don’t think anyone has ever laughed at it: my father is an electrician; my brother is an electrician; so, what else can I become but a neurologist?

Perhaps my father would have preferred me to share his love of TV cables and plug sockets, but I don’t think he’s entirely unhappy that I’m all about the electrical currents in our bodies. Anyway, that’s what I say when I’m asked why I choose neurology.

I say that because otherwise I would have to start rambling. Because, unlike my cardiology-enthusiast friends, I’m not fascinated by a single organ. It is also not because I particularly like having or not having a scalpel in my hands. It has more to do with the fact that I like things to be simple. Not in the sense of uncomplicated or banal, but fundamental. I like to get to the bottom of things. I like to look for the roots. And in my eyes, there is no more fundamental, more centre-focused discipline than human medicine and, within its specialities, none more fundamental than neurology.

What I want to say has certainly been said by many others before me. But I first saw my thoughts spelled out on paper in the neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi’s memoir, When breath comes air. He explains that he studied literature and philosophy to try to understand the meaning of life, and that he studied neuroscience to understand how the brain could enable an organism to attribute meaning to life in the first place. These lines took my breath away at the time.

First of all, this idea that art and philosophy could exist alongside the natural sciences left me speechless – this rebellion against choosing one single field of interest, against only scratching the surface, against being a blinkered specialist. It is the concept that we can look for as many approaches to understanding the world as we want, and that there is no right or wrong approach: physics tries to make out rules and patterns in nature; art tries to reflect how we experience this exact nature; and philosophy tries to put it into words and thoughts. All sciences and arts are different ways in which we try to get to the bottom of ourselves as well as everything around us.

Second, Kalanithi says what the philosopher Immanuel Kant has said more than 200 years before him: man cannot be excluded from any interpretation, any calculation or any piece of art. Through our existence, we place a filter on everything we experience. So, what could be greater and more fundamental than studying humans themselves? Not to analyse from a certain perspective, but to analyse the perspective itself? The perception, the consciousness, the nervous system?

That’s what I meant – my heartfelt answer to “Why neurology?” is a little long-winded. It is probably also an out-of-reality, slightly pretentious, utopian answer. I understand that, with the pace at which our world and medicine are developing, everyday life cannot revolve around such questions only. Our world requires a certain specialisation, a narrowing of the horizon, so that we can function in it. Nevertheless, it is my wish and my goal to somehow integrate these ideas into my day-to-day life as a doctor. To apply them to the stories people tell me about their pain, and hopefully also about their healing. To make this zooming in and out of human life a habit, in order to work with more foresight, research more accurately and simply learn more.

I don’t want to forget what medicine and neuroscience actually are: one of many tools with which we can make the world, ourselves and our place in it a little more comprehensible. I want to remember that I chose neurology because, in reality, I didn’t want to choose anything. Or everything.

And probably because my father is an electrician.

Melissa Szmukala, Poland, 6th year Student

Health is a privilege. That doesn’t sound right, does it? Health is a basic human right!

Abstract

I believe that health equity is one of the highest goals we, as a society, need to achieve.

The ‘One Health’ concept combines human, animal and environmental health for a unified global health approach. To strive for equity through ‘One Health’: that is why I have chosen a future in global health.

To a neurologist, the field of neurology might seem like one of the most important in medicine – there is no functioning of the body without the nervous system. But within the context of global health, neurology is often overlooked calling for headlines such as “Study Reveals Link Between Air Pollution and Neurological Disorders, Prompting Global Health Concerns”. We don’t talk about epidemic meningitis outbreaks, a lack of medication for epileptic disorders in low-income countries or much of global health issues (that do not concern Europe or North America).

That has to change.

Introduction

“When I grow up, I will make everyone healthy.” That is what three-year-old me used to say (according to my aunt). Ever since I can remember, I wanted to help people. That was my chosen fate in life. In kindergarten I broke my arm, because I was protecting my friend from a bully and he happily pushed me down the stairs instead. Tutoring was the weapon of choice in battling inequality in high school. A battle, because I have rarely had any challenge as hard as teaching first graders how to read! With my desire to see the world and truly learn about its secrets, life brought me to a clinic in India. During my time there, I understood for the very first time why we need equity in the world, why equality is not enough. At just 18, I understood how cruel disease, especially neurological, can be to those who don’t have the means to overcome it. So, I decided that I will help them.

And “Why Neurology”? Albert Einstein said “the most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science”. Because mystery brings wonder, excitement, and passion. Neurology combines all three for me.

I have almost made it to my medical school graduation and I am now realising that this was the warm-up. With the whole wide world right in front of me, choices to make, more things to learn, and people to help – the real work is only about to begin.

Main Part

Like no other disease in the past century COVID-19 changed the world. Global health and an understanding of the ‘One Health’ concept have re-entered the public sphere. We need to use this momentum to shift the conversation, away from what looks good on paper to things that have a real impact. Bringing the focus back to what is important: how to overcome the health disparities.

‘One Health’ is human health.

In Kenya, medication for Parkinson’s disease is difficult to come by. Levodopa is available in about half the pharmacies nationwide. Meanwhile, if they are available, patients can barely afford them. Healthcare should not be dictated by whether you can afford it or know the right people.

‘One health’ is animal health.

Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of a neurological zoonotic global health concern is the bovine spongiform encephalopathy – mad cow disease. The transmission of Creutzfelt-Jakob disease from cow to human was born from a practice that neglected animal health and its consequences. Ingestion of contaminated meat can lead to disease and quick death without hope for curative treatment.

‘One Health’ is environmental health.

Air pollution has recently been linked to an increase in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and neurodevelopmental disorders, both in pregnancy and childhood. As an invisible trigger it contributes to CNS pathology through neuroinflammation, microglial activation, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and alterations in the blood-brain barrier. It literally changes our brain.

Conclusion

A global implementation of the ‘One Health’ approach is necessary to create the change we need to see in the world. As I begin my journey as a doctor, I am constantly reminded of why I chose the medical profession. It is my mission in life with a vision for a better future. “When it comes to global health, there is no ‘them’… only ‘us.” – Global Health Council. So let us create meaningful change to build a world where health is not a privilege, but a basic human right.