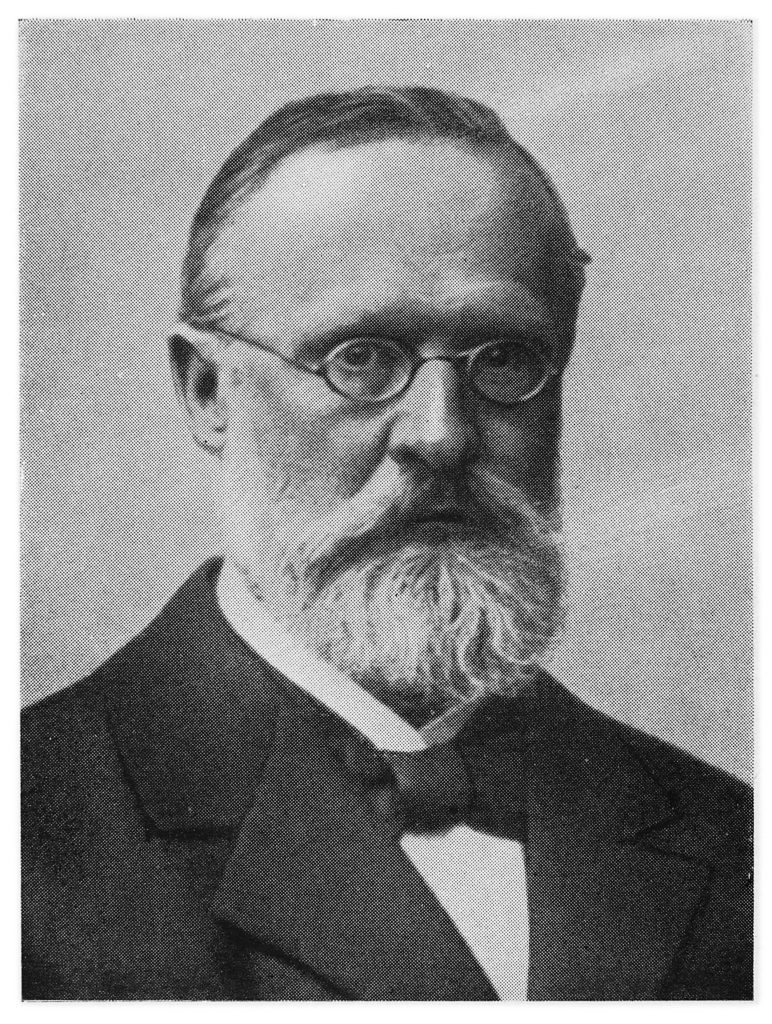

The roots of clinical neurology can be traced back to Germany. With his ”Lehrbuch der Nervenkrankheiten des Menschen“ (textbook of human nervous diseases) 1840, Moritz Heinrich Romberg (1795 – 1873) established the foundation of clinical neurology as we know it today. His work was the first and for decades the only systematic representation of neurological diseases in Europe and America, bringing him international fame and esteem. In 1863, Fjodor Dostojewski consulted Romberg in Berlin for his epilepsy, as he was by then a well-known specialist in Europe (J. L. Rice 1985). In 1981, Spillane named Romberg” the first clinical neurologist “and Klavans wrote in 1982: “Modern neurology begins with Romberg “[1] . It is not for nothing that the EAN awards a Romberg Prize.

The term neurologist indeed dates from 1832, the year that Romberg introduced the work of Charles Bell to his Berlin audience.” Moritz Heinrich Romberg translated the first edition of Sir Charles Bell’s anatomic book on “The Nervous System of the Human Body” into German. Adopting Bell’s and Francois Magendie’s distinction between motor and sensory nerves and spinal root portions, Romberg was the first to formulate an analytical structural-functional approach towards examining and understanding disease-related dysfunction, mainly of the peripheral and spinal nervous system. “Neurology as we know it today, in practice and clinic, developed after he published the first edition of his “Lehrbuch der Nervenkrankheiten”, the first volume in 1840 and a final one in 1846.” [2] An influential English edition was issued in 1853 in London. Born in 1840, Wilhelm Erb possibly “was the most brilliant clinical neurologist of the latter part of the nineteenth century”. [3] After having gained experience in pathology and internal medicine, and stimulated by teachers such as Friedreich and Duchenne, Erb’s further work was mainly devoted to spinal and muscular disorders, but also to electrotherapy. He was among the first who regularly used the reflex hammer and put forward the need for neurological specialization and education. Thus, “perhaps his greatest gift to neurology was in the field of teaching, for it is to Erb we owe the development of an orderly and systematic manner of examination, so fundamental to diagnosis”. [4]

Among his scholars were Adolph Struempell, Max Nonne, and Johann Hoffmann.

Different from the trained “internists” Romberg and Erb, Carl Wernicke, born in 1848, came from the field of psychiatry. Accordingly, his main interest was the analysis and understanding of brain dysfunction. Shortly following Broca’s observations published in 1861, Wernicke further conceptualized “topic” models of higher-order dysfunction such as aphasia. He envisioned that these might hopefully be able to unify neurology, psychology and psychiatry later.

Born in 1864, Alois Alzheimer was among the first to use microscopy of stained postmortem brain slices for the study of neuropsychiatric conditions. Together with Franz Nissl, he histologically characterized progressive paralysis, arteriosclerotic brain damage and, in 1906, another “peculiar affection of the cortex” later named after him by Emil Kraepelin. Alzheimer was confident that tissue characterization, but not functional localization, would prove to be the key to a better understanding of brain disorders. “Indeed, I believe to have found the electroencephalogram of man and now publish this for the first time” were the famous words written by 56-year-old Hans Berger in 1929, 5 years after his original recording. Having entered the Psychiatry Hospital in Jena 1897, at that time led by Otto Binswanger, Berger’s goal had always been the objective measurement of “psychic energy”.

The importance and autonomy of neurology in Europe were strengthened considerably during and after the Great War 1914-1918. This was particularly so in Germany where neurology had remained integrated into psychiatric institutions in most universities and hospitals since the 19th century. This differed from the English or French-speaking countries of Europe and America and also stood in contrast to the considerable number of internationally renowned “pure neurologists” in Germany before the world wars.

Following a “golden century” that had started with Moritz Heinrich Romberg in 1832, German neurology entered its dark age in 1933. Legislation implemented by the “Nazi“-party banned many Jewish fellow citizens including physicians from their professions and from using their possessions. One-third of the German physicians were Jewish which led to the turnout of many, if not the most of the nationally and internationally renowned German neurologists. But this was not the only devastating consequence of a radically racial and “eugenic” policy in Germany between 1933 and 1945 that remained unopposed by the silent majority. Many university chairs and other leading positions were filled politically, and neurology and psychiatry were “reunified” in 1935. Simultaneously with the beginning of World War II, Adolf Hitler personally initiated the planning and organization of systematic killings of chronically hospitalized neuropsychiatric patients. After the transportation of their victims to dedicated killing facilities throughout Germany, approximately 70.000 “lives unworthy of life” were extinguished between January 1940 and August 1941 in gas chambers, by starving or injections. The mental framework of this grim period also lowered the ethical standards and thresholds for some neurological studies in human patients. After this deep fall within only 12 years, it took two decades for German neurology to regain scientific orientation, organization, and international acceptance gradually. It was a restart from almost point zero in a divided country.

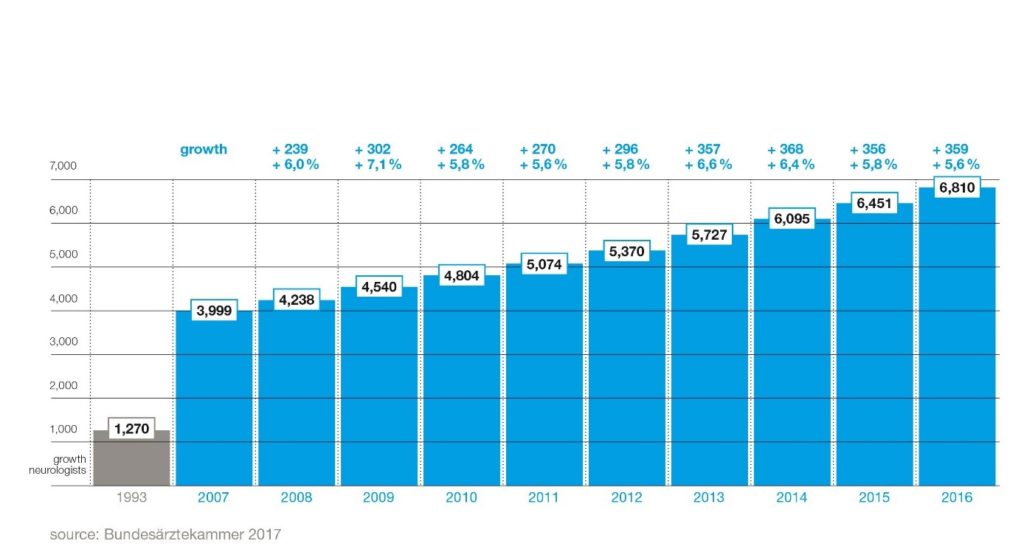

Today, neurology develops as rapid as never before. Twenty years ago, there were only around 1,500 neurology specialists in Germany. Today, over 7,000 neurologists provide care for up to 3 million patients each year in German hospitals (comprising 357 acute care units, 110 specialist units, 143 rehabilitation units, and 40 university hospitals) and approx. 2,500 out-patient practices. [5] In Germany, there is one neurologist for every 12,000 inhabitants. With an annual growth rate of 6 percent, neurology is growing faster than any other medical specialty. These days, there are more practicing neurologists in Germany than there are dermatologists, urologists, or ENT specialists. [6] In 2016, the number of new license admissions for specialists in neurology reached a record high of 527. This is due not least to the success of the German Neurological Society’s intensive work with junior doctors and its next generation organisation, the Young Neurologists, which celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2017. Neurology in Germany is a developing medical science with a promising future. Two-thirds of all specialist doctors are under the age of 50. The proportion of women in neurology has been growing steadily for years – as it has in the whole of German medicine. In 1993, the figure was only 27 percent, by 2016 it already reached 44 percent, and the trend continues to point upwards. The next generation of medical professionals is also already predominantly female: 61 percent of specialist licenses were issued to female doctors in 2016.[7]

Upon completion of an undergraduate degree course in medicine, a young doctor in Germany can continue his or her studies to become a consultant neurologist in at least 5 years (60 months). One typically starts out as a junior doctor in a certified neurology hospital for advanced training. Every hospital has its rotation programme so that with each rotation the skills required to complete the specialist doctor catalogue can be acquired. Besides, a resident doctor is required to spend 12 months working in a psychiatric unit. In up to 12 months of further training, credits can be accumulated in other medical specialties such as internal medicine, general medicine, neurosurgery, neuropathology, or neuroradiology. Up to 24 months of accredited training may be attained in the outpatient sector. This training typically takes place in the German language, just like the medical degree itself. Neurologists from abroad who would like to work in Germany need to have very good German language skills. The minimum requirements are a B2 language certificate for general language and a C1 specialist language certificate for medicine.

Neurologists today deliver a crucial component of medical care in Germany. Since 12-16 percent of patients in German Accident and Emergency (A+E) units come in with neurological symptoms, neurologists are employed in many A+E units. Stroke care is practiced nationwide in stroke units led by neurologists. From around 500 stroke units more than 300 are certified. Also, centers equipped to perform a mechanical thrombectomy cover all regions of Germany. Thanks to this infrastructure, more than 70 to 80 percent of all patients have access to the best possible care very quickly after a stroke. As a result, the mortality rate following a stroke has more than halved (1998: 150 per 100,000 inhabitants; 2015: 69,8 per 100,000 inhabitants). Several specialty hospitals devote themselves to neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis or dementia. There are also numerous specialists for orphan diseases.

In Germany, practically every resident has health insurance and a free choice of the doctor. Almost 90 percent of Germans are covered by statutory health insurance, while around 10 percent are privately insured. The primary medical care of the population is thus assured. Although neurology is growing faster than any other medical field in Germany, patients often need to wait a long time for an appointment in a neurological out-patient practice. Neurology, therefore, must and will continue to grow in Germany.

Today’s German Neurological Society, initially founded in 1907 and temporarily dissolved in 1935, was re-established not before 1950. It took until 1951 and 1955 for the first “new” neurology chairs to be created in Freiburg (Richard Jung) and Düsseldorf (Eberhard Bay). The gradual recovery of neurology in the early post-war period was driven by only a few local neurological “schools” and key figures. Heinrich Pette, chairman in Hamburg-Eppendorf since 1934, remained a particularly important teacher in the initial phase. He also was the first president of the German Neurological Society reinstituted in 1950. Already starting in the 1950`s, the spectrum of neurology was increasingly broadened by scientific and methodological inputs from experimental and clinical neurophysiology. Particularly influential pioneers of this development were Richard Jung (“Freiburg school”) and Albrecht Struppler (Munich), with many of their scholars still being active today. They founded dedicated neuroradiology sections within their neurology departments and strongly promoted functional neurological surgery. Neurovascular ultrasound was among the methods specifically elaborated in Freiburg, and it was this generation and the return to scientific mind-openness that began to pave the way for today’s (re-)internationalization of German neurology.

As the expert association of all neurologists in Germany, the German Society of Neurology amounts to almost 9,000 members at the beginning of 2018 and is thus the largest national neurological society in Europe and among the five largest worldwide. Membership has more than doubled in the last 15 years. Every year, membership grows significantly. Particularly in recent years, many resident doctors have joined – making the DGN a young association.

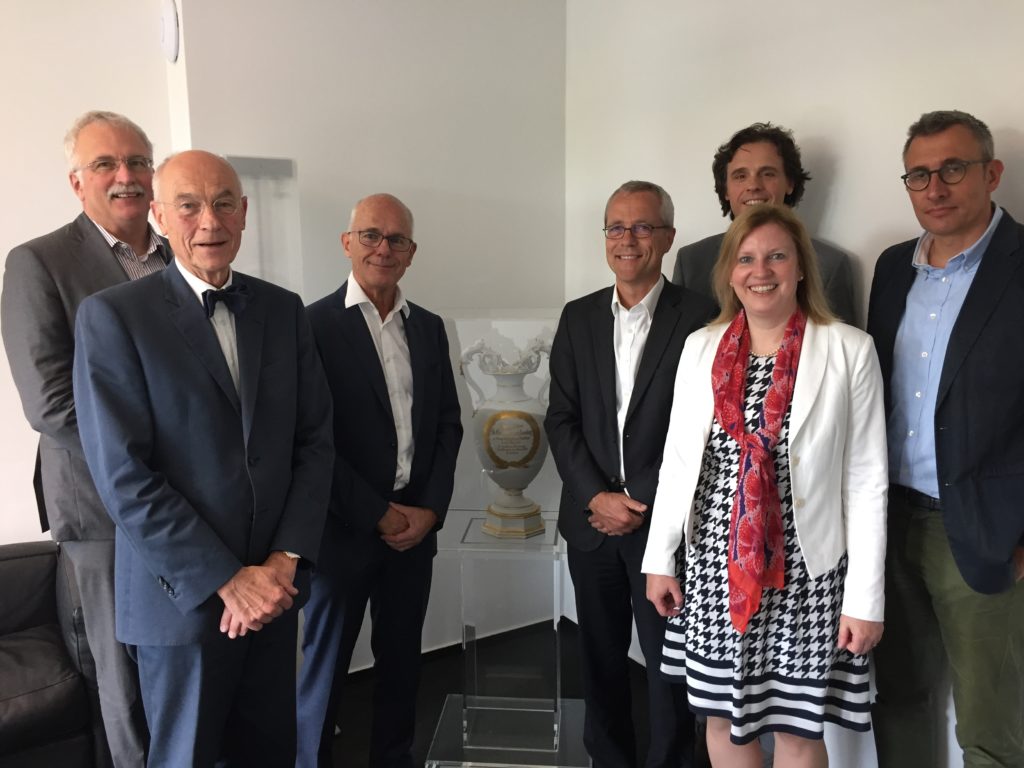

DGN-Board 2018:

From left to right: Prof. Dr. med. Ralf Gold, Dr. rer. nat. Thomas Thiekötter, Prof. Dr. med. Peter Berlit, Prof. Dr. med. Gereon R. Fink, Prof. Dr. med. Gereon Nelles, Prof. Dr. med. Christine Klein, Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Gerhard J. Jungehülsing

© DGN

The German Neurological Society has developed into a strong society and an increasingly influential voice within the healthcare system. Key assets of the DGN are an annual congress with 6,000 visitors (i.e., as many as the EAN Congress), around 80 medical guidelines, and an elaborate Education Academy conducting around 50 CME courses each year. The German Society of Neurology supports an active community of students and young doctors, the Young Neurologists. Most of them are working as residents in neurological institutions. Since 2007, the DGN has a full-time managing director, Dr. rer. nat. Thomas Thiekötter. In 2018, Prof. Dr. Peter Berlit became the first secretary general. Seven members of staff are based at the head office in Berlin. The current executive board comprises the president Prof. Dr. med. Gereon R. Fink, Cologne, vice president Prof. Dr. med. Christine Klein, Lübeck, past-president Prof. Dr. med. Ralf Gold, Bochum, secretary Prof. Dr. med. Gereon Nelles, Cologne, and treasurer Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Gerhard J. Jungehülsing, Berlin.

A current study conducted by Cruccu et al. shows that Europe as a whole is at the same eye level as the USA in regard to the „gross neurological product “ (which includes all articles published in any indexed journal)“.[8] “Restricting the search to top neurological journals showed that, since 2012, European production grew faster than that of the USA. Germany had the highest production within Europe”.[9]

Article contributed by Peter Berlit, Frank Miltner, Helmuth Steinmetz, Gereon Fink

Sources:

[1] Source: https://www.dgn.org/rubrik-dgn/972-die-romberg-amphore-ein-gruendungsdokument-der-neurologie

[2] Viets HR. The history of neurology in the last one hundred years. Bull NY Acad Med 1948, 24: 772-783.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Source: DGN

[6] Source: statistics of the German Medical Association

[7] ibid.

[8] G. Cruccu, G. Deuschl, A. Federico. Scientific publications of European neurologists: a survey commissioned by the European Academy of Neurology. European Journal of Neurology 2018, 0: 1-6.

[9] ibid.