by Ivan Iniesta

INTRODUCTION

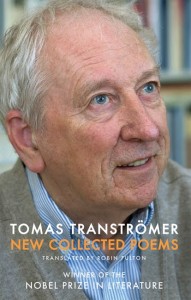

In 2011 the widely acclaimed Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer (b. Stockholm, 1931) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality”(2). This article celebrates the poetry of Tomas Tranströmer, a poetry which includes two late collections of poems remarkably written to a large extend after losing his speech.

MUSIC BASED POETRY

MUSIC BASED POETRY

In November of 1990 Tranströmer became severely dysphasic and lost the use of his right hand as a result of a stroke. As if anticipating his own fate, in his longest poem Baltics (Östersjöar, 1974) he had referred to the story of a Russian composer who became speechless and hemiplegic after a brain bleed:

“Then, cerebral hemorrhage: paralysis on the right side with aphasia,

can grasp only short phrases, says the wrong words.

Beyond the reach of eulogy or execration

But the music´s left, he goes on composing in his own style,

for the rest of his days he becomes a medical sensation.

He wrote music to texts he no longer understood-

in the same way

we express something through our lives

in the humming chorus full of mistaken words” (3)

Himself a lifelong amateur pianist, Tranströmer also carried playing the piano with his left hand after the stroke, some contemporary pianists composing left handed pieces for him inspired by his post-stroke collection of verse, The Sad Gondola (Sorgegondolen, 1996), such as the Tranströmer Settings for the New European Ensemble’s 2010 tour of Sweden.

Some famous musicians like Ravel, [Richard] Strauss and Prokokiev had already written left-handed piano compositions. In 1928 Maurice Ravel composed The Concerto For The Left Hand in B Major for Paul Wittgenstein, the Austrian pianist who had lost his right arm in the Great War, which enabled him to resume concert performances. Ten years later, in 1933, at the age of 58, the French composer came to the end of his musical career after losing his own speech through a brain insult – of a more progressive nature than that of Tranströmer – that rendered him unable to express musical ideas either in writing or performance (4).

Greatly influenced by the rhythms of classical music, Tranströmer’s poetry is also full of references to music and musicians like Haydn, Schubert, Balakirev, Grieg, Wagner or Liszt. Capable of only uttering a few words since he suffered the stroke, Tranströmer can still express himself through music and enjoys playing some pieces composed for the left-hand by Czech composer Fibich and by the Spanish pianist Mompou.

Featuring in Baltics, Vissarion Shebalin lost most of his language following a stroke in 1959 but continued composing and completed his fifth symphony, which was regarded by his close friend and colleague Dmitri Shostakovich as a brilliant creative work, filled with the highest emotions and full of life. As far as Tranströmer is concerned, he regarded Baltics as his “most consistent attempt to write music (5)”.

PRE-STROKE POETRY

Following the publication of his first poetry book 17 poems (17 dikter) in 1954, Tranströmer has published a collection of poems more or less every four years that is until the year of the stroke (1990), aged 59. Since then, there have been only two more collections of newly published poetry, although some of the poems included in those had been written before the stroke.

The first book of poems published by Tranströmer after the stroke (The Sad Gondola, 1996) was inspired by Liszt’s utterly depressing La Lugubre Gondola, which the Hungarian composer had written whilst visiting his daughter and son-in-law Richard Wagner in Venice. Interestingly, in a letter to his friend and partial translator, Robert Bly, written six months before he suffered the stroke, Tranströmer recalled a recent three week holiday in Venice with his wife Monica (6). His epic poem The Sad Gondola recreates the encounter between the two great musicians and was probably written on returning from Venice and before having the stroke. Likewise, the poem The Cuckoo, given its narrative nature, was probably conceived and written before the stroke. The opening lines of his book The Sad Gondola correspond to those of the poem April in Silence:

“I am carried in my shadow

like a violin

in its black case” (7)

However, this is a poem he had already read aloud and was therefore written before the stroke (8).

Tranströmer’s Memories look at me (Minnena ser mig, 1993) is an extraordinary autobiographical account of the author’s childhood and adolescence experiences which ends just before he embarks in his life-long career as a poet. Published three years after the stroke, these writings are likely to have been written before the stroke, subsequently assembled and probably revised and edited ahead of publication. The title of the autobiography is that of a poem published in his 1983 collection of poems. Responding to a Swedish journalist hours after receiving the Nobel Prize, Tranströmer recommended Memories look at me as a good introduction to his poetic oeuvre (9).

STROKE AND MOTOR (BROCA) APHASIA: THE CONTIGUITY DISORDER

Neurology as a medical specialty was founded in the late 19th century on the basis of localizing dis-functioning structures of the brain according to the anatomico-pathological method. A founding cornerstone of this approach was the 1861 structural localization of expressive language, which was found to reside over the foot of the third left frontal convolution, confirmed by a brain necropsy on a patient of Paul Broca who had suffered from a 20-year history of non-fluent aphasia (10). And so were the evolutionary ideas of John Hughlings Jackson on the dissolution of the nervous system, largely based on his clinical observations of aphasic patients. Since then, neurologists have recognized that almost all patients with expressive aphasia have some degree of difficulty in writing (dysgraphia). In the 20th century A.R. Luria nicely demonstrated how the functions of the brain can be better understood by studying damaged faculties, hence inspiring his fellow countryman Roman Jakobson’s linguistic theories on the two main types of aphasias: motor (alias Broca) and sensory (alias Wernicke). According to Jakobson, those patients who developed predominantly motor aphasia would lose their “ability to propositionize. The context disintegrates. First the relational words are omitted, giving rise to the so-called telegraphic style”(11). The contiguity here is severely affected, giving rise to the loss of relational words and the syntactical pattern, hence resulting in “agrammatism”. Contrary to those affected by a predominantly sensory aphasia, the ability to produce metaphors and the “thesaurus” capacity to find similarities remains relatively intact in patients with efferent or motor aphasia. There is a “regression –Jakobson also uses the Jacksonian term dissolution– towards early infantile stages of language”(12). Such theory was put into practice by Tranströmer himself in his post-stroke? Poem Like Being a Child:

“Like being a child and a sudden insult

is jerked over your head like a sack

through its mesh you catch a glimpse of the sun

and hear the cherry trees humming

No help in that – the great insult

covers your head your torso your knees

you can move sporadically

but can´t look forward to spring

Glimmering woolly hat, pull it down over your face

stare through the stitches.

On the straits the water-rings are crowding soundlessly.

Green leaves are darkening the earth….” (13)

Non-literal language functions linked with the non-dominant right hemisphere and hence preserved in a left hemispheric insult and in particular when emissive or motor aphasia predominates over receptive or sensory aphasia include the use of metaphors, irony, humour, prosody, story comprehension, inference, working memory and behavioural understanding drawing on the beliefs and emotions of other people (theory of mind) as well as music and melody. On the other hand, a severe non-fluent aphasic can only communicate using non-verbal communication skills such as body language and supported communication. Such support is admirably illustrated by Monica Tranströmer during an interview offered by Tomas Tranströmer only hours after he was awarded the Nobel Prize (14).

POST-STROKE POETRY: THE GREAT ENIGMA

Tranströmer’s career as prison psychologist became a significant source of his poetry, as he explains on an interview with Ann Victorin held in Västerås in 1989 and reproduced on BBC Radio 3 in 1990 (15). He was nevertheless surprised not to have been asked more often the opposite question, concerning how his poetry may have affected his work (16). The vast majority of the poetry written by Tranströmer after the stroke consist on haikus: a Japanese poetic form referring to nature which are compressed into three lines and a total of 17 syllables (5-7-5) cutting words. However Tranströmer had already cultivated the haiku since the 1950s. And if we compare a group of nine haikus from Hällby Young Offenders’ Prison written in 1959 (but only published in the 21st century) with those of The Great Enigma (Den Stora Gåtan, 2004), which to a large extend were written after the stroke we can find no significant differences. For, haikus escape syntactical patterns and are intrinsically agrammatical and telegraphic in style. To illustrate this,here is a haiku from his 1959 Prison (Fängelse)

“The boy drinks milk and

Sleeps securelcy in his cell,

A mother of stone.” (17)

And now from his 2004 collection:

“Here’s a dark picture.

Poverty painted over.

Flowers in prison dress.” (18)

Deprived from his speech, there is hardly any correspondence or narrative poetry left of Tranströmer after the stroke. A poet of concentration prior to the stroke, his poetry became increasingly compressed since the 1980s, as Robert Bly pointed out, but only after the stroke did it become disproportionately brief compared to his pre-stroke production, confining most of his poetry to haikus.

Prior to the stroke a non-prolific writer, after it Tranströmer therefore became even more abbreviated in his writing, through what Seshadri called –in reference to aphasia– the “inner weather of pure meaning” (19). Or, to paraphrase the Swedish poet and Tranströmer expert Niklas Schiöler (author of the thesis on Tranströmer “The Art of concentration” (20)), this increased and to a large extend involuntary concentration of his poetry has resulted in Tranströmer becoming more Tranströmer-like.

What makes Tranströmer a medical sensation –somewhat prophetically announced in Baltics-, is the fact that he managed to continue translating his ideas and images into words, creating language in the absence of speech, in poetry written in accordance with his own prophetic (pre-stroke) motto and last verse of From March 1979 (Från mars – 79):

“Weary of all who come with words, words but no language

I make my way to the snow-covered island.

The untamed has no words.

The unwritten pages spread out on every side!

I come upon the tracks of deer in the snow.

Language but no words” (21)

As the next anniversary of the Nobel Prize in literature approaches, we celebrate the translucent poetry of Tranströmer who was able to turn adversity into opportunity and through music and poetry overcome the great communication barriers imposed by the stroke. A rare living prophet in his own homeland, Tranströmer produced some poetry of the highest calibre, despite severe expressive dysphasia and dysgraphia.

(1) This work is an extension of the abstract entitled “Tomas Tranströmer’s stroke of genius: language but no words”. Short Communications 2: History of neurology, Neurology and Arts SC218. EFNS 2012 and is largely based on the paper Iniesta I. Tomas Tranströmer’s stroke of genius Clin Med 2012; ahead of print, as well as a forthcoming book chapter on “Literature, Neurology and Neuroscience”.

(2) Prof P. Englund’s Nobel Prize Announcement on 6th October 2011. Presented by Nobelprize.org

(3) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

(4) Alajouanine T. Aphasia and artistic realization. Brain 1948;74:229–241.

(5) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

(6) Tranströmer T, Bly R, Schmidt T, Svensson LH. Air Mail: brev 1964 – 1990. Bonnier: Stockholm, 2001.

(7) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

(8) Robertson-Pearce P, Astley N. Tomas Tranströmer. Film available at YouTube.

(9) Interview in Tranströmer’s Stockholm home after the Nobel Prize. Presented by Nobelprize.org

(10) Broca PP. Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche. [Sur le siège de la faculté du langage.]. Bulletin de la Société d´Anthropologie 1861; 2: 235–238.

(11+12) Jakobson R. Studies on Child Language and Aphasia. The Hague: Mouton; 1971.

(13) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

(14) Interview in Tranströmer’s Stockholm home after the Nobel Prize. Presented by Nobelprize.org

(15) Robertson-Pearce P, Astley N. Tomas Tranströmer. Film available at YouTube

(16) Tranströmer T. The Half-Finished Heaven. Translated by Robert Bly. Graywolf Press: Minneapolis, 2001.

(17+18) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

(19) Seshadri V. Aphasia. The New Yorker 2004; April 12 issue:42.

(20) Schiöler N. Tolkningar/redaktör. Stockholm: Bonnier, 1999.

(21) Tranströmer T. New Collected Poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. Bloodaxe Books. Printed by Bell & Bain: Glasgow; 2011.

Ivan Iniesta is neurologist, working at The Walton Centre in Liverpool, UK.