Prof. Angela Vincent

Emeritus Professor, University of Oxford

Fellow of Somerville College, Oxford

Awardee of the Camillo Golgi Lecture at the 3rd EAN Congress in Amsterdam 2017

Elena Moro: Dear Prof. Vincent, you have recently been awarded with the WFN Medal for Scientific Achievement in Neurology. We congratulate with you for this well-deserved outstanding recognition!

In light of your longstanding experience in the world of neuro-immunology in particular, what do you think is it the most recent important discovery in your field?

Angela Vincent (AV): Well first of all thank you for the congratulations. I am thrilled to receive the WFN Medal and it is much appreciated.

Neuroimmunology is a relatively recent discipline – probably only first defined in the 1980s. It includes not only the work on antibody-mediated diseases, which is my interest, but also experimental and clinical work on multiple sclerosis and other disorders and, more recently, growing attempts to demonstrate a role of the immune system in neurodegenerative diseases.

In terms of direct clinical relevance to these diseases, there is no doubt that the development of drugs, mainly monoclonal antibodies, that target different cells or processes of the immune system has proved very important for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and increasingly other conditions. On a smaller scale, but equally exciting, is the growing number of antibody-mediated disorders of the central nervous system (CNS) which often respond to other, more conventional, immunotherapies such as steroids, plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulins.

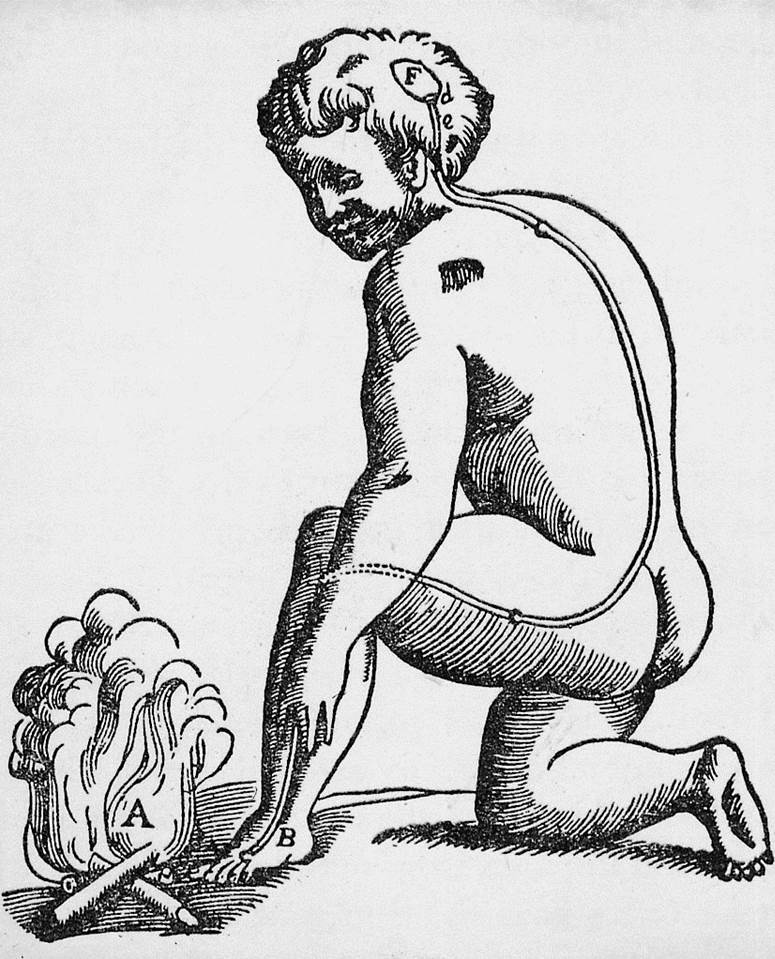

This field really started in the 1970s with the discovery of antibodies to the acetylcholine receptors in myasthenia gravis but until the 1990s, new discoveries were made essentially only in the peripheral nervous system. The change to the central nervous system started almost 20 years ago when we first began to identify “voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC)” antibodies in patients with peripheral hyperexcitability syndromes, some of whom had evident central nervous system symptoms. The first patients with predominant CNS disease with highly raised VGKC-antibodies had limbic encephalitis and Morvan’s syndrome respectively (both published 2001). Previously, limbic encephalitis had mostly been considered “paraneoplastic” with antibodies against intracellular proteins such as “Hu” and “Yo” and these antibodies were not associated with immunotherapy-responses, but one of our two patients with classical limbic encephalitis had no tumour and recovered spontaneously over-time, whilst the other had myasthenia gravis associated thymoma and recovered with immunotherapies. These case reports, and the Morvan’s syndrome patient who also responded very well to plasma exchange, provided the first strong clinical evidence that antibodies could cause CNS disease, and questioned the old dogma that antibodies could not get into the brain. It was only later that we showed that the VGKC-antibodies targeted associated proteins, CASPR2 and LGI1, rather than the VGKC itself. CASPR2 antibodies are frequently found in Morvan’s syndrome and LGI1 antibodies in limbic encephalitis. A very interesting discovery by my former clinical fellow, Dr Sarosh Irani and his collaborators, is of a specific and previously unrecognised form of epilepsy – now known as faciobrachial dystonic seizures – that is strongly associated with LGI1 antibodies and often predates the development of limbic encephalitis. Dr Irani now heads the Oxford group.

There is no doubt, however, that the discovery by Prof Josep Dalmau’s group of the NMDAR-antibody form of autoimmune encephalitis in 2007, which mostly presents in young female adults and in children of both sexes, is the most important, treatable antibody-mediated disease. The movement disorder with loss of consciousness and autonomic instability that these patients develop, often means many weeks or months in intensive care, with the need for multiple immunotherapies and symptomatic treatments before they begin to recover. Strikingly, recovery is often very good and even apparently complete. Working as I have been doing with the paediatric neurologists in the UK and elsewhere to help diagnose and study this condition in children has been a privilege and very satisfying.

Scientifically, there is still much to be discovered. We don’t really know fully the mechanisms by which the NMDAR and other antibodies cause disease. There are lots of unanswered questions but there are limitations on experimental models for these disorders – and the number of laboratories with experience in their use – and the questions are not easy to answer in man. However, one aspect that is definitely beginning to have an impact is the use of cutting edge imaging techniques to map the structural and functional changes in brain connectivity during and following treatments for the antibody-mediated conditions. Up till now the results are partly confounded by heterogeneity in the patients, their treatments and duration of disease, but there are certainly some interesting observations being made, including changes in brain structure or function that may not only reflect the effects of the antibodies, but may also be secondary, compensatory changes that occur over time.

EM: What importance takes the study of neuro-immunology when considering clinical neurology?

AV: Because the recently discovered antibody-mediated diseases are immunotherapy responsive, their identification in patients usually leads to immunotherapies. It is thought that prompt treatment leads to quicker results, and less time in intensive care, although it is difficult to be certain as patients are very variable in their severity and the natural progression of the disease. In any case, the response to treatment, even if it requires patience and perseverance, means that the neurologists are very keen to identify the patients. For this reason, although the individual antibody-mediated disorders are all rare compared with common disorders like Parkinson’s, their identification has made a real change in the manner in which clinicians approach patients with unexplained memory problems, seizures, psychiatric features and movement disorders. Many now think “could this be an antibody-mediated disease?” This is a real change from former decades.

EM: Can you tell the readers of EAN Pages about your career? What brought you to the study of neuro-immunology and the worldwide character of your work?

AV: I usually describe my career as a mixture of “science and serendipity”! I qualified as a doctor in the 1960s and enjoyed my first year of internship but I found clinical medicine at that time to be often lacking in scientific background – and also lacking in clinicians who wanted to investigate the mechanisms of disease. I decided to study biochemistry which gave me the credentials to do laboratory work, and I planned to spend my time in the basic sciences which appealed to me intellectually. By a series of lucky accidents I got involved with some of the early studies of acetylcholine receptors with Ricardo Miledi at University College in London, and this led to our first work on myasthenia gravis collaborating with the neurologist John Newsom-Davis. It was not long before I joined John at the Royal Free Hospital in London, where together we set up the Neuroimmunology Group. Ten years later 16 members of the Group moved to Oxford when John became Professor of Neurology there, and the Group has flourished since then. We began to attract visiting clinical fellows from around the world and that meant that international collaborations were set up. When I took over as leader, on Johns’ retirement in 1998, I was able to expand our interests from the periphery, where we had focused mostly on myasthenia gravis and the Lambert Eaton syndrome, and begin to move cautiously towards the CNS. At the same time, as our interests widened, so also did the need for the clinical diagnostic service that I had established, and this became a centre for the testing of antibodies in samples sent from around the globe, first from previous fellows and then increasingly from those who had read our publications. Trying to help these doctors to diagnose their patients was gratifying both personally and also in helping to extend the clinical features encountered. In rare cases it led to identification of new antibodies. I feel that the WFN Medal is at least partly justified by my efforts to harness our expertise to help others.

EM: Your outstanding work and teaching experiences stand as a role model for scientists and neurologists in training. What would be your advice to neurologists who start up their career?

AV: My advice is rather simple and is the same to everyone whatever their field. Find out what you are good at and do it as well as you can. For the clinical doctors, identify novel phenotypes and write them up – they often stimulate research and new ideas and may help you get a Fellowship to pursue them. For those already in a laboratory, don’t ignore experimental results that don’t fit neatly into your expectations, but use them to stimulate new ideas. Pursue these ideas first with simple experiments or collaborations, and then let them help shape your future career.

Good fortune and serendipity really has played a large part, but nothing would have been possible the without bright young people, both clinicians and basic scientists, who have spent time in our lab, and the wonderful, supportive and enthusiastic longer-term colleagues who have been the backbone of our Group over more than 30 years.

by Elena Moro, Editor-in-chief EAN Pages