Belief in progress is dauntless. Media keeps informing about inventions which, very soon for certain, will lead to victory over cancer or Alzheimer’s disease. The literary set, some conservative politicians or church officials sometimes doubt the progress, their scepticism is often motivated ideologically and hardly resonates among doctors or scientists. Because we experience the progress on-line – the flow of information, more or less important, patents, new medicaments, publications, costs of health care rising to astronomic heights – do we witness and act as in a revolution in medicine? No, we do not, at least not in neurology and not such a revolution as for example introducing antibiotics into practice.

I think that the last step of development related to the entire field of neurology was the introduction of CAT in the 1970s. A considerable change for some (rather small) groups of patients was a biological therapy of multiple sclerosis or thrombolysis in stroke or a discovery of a new and curable mechanism of a disease – for instance in autoimmune diseases in encephalitis or neuromuscular diseases. The boom of genetics has not excessively influenced the therapy of diseases of the nervous system. Progress can be seen from three perspectives – a patient, a disease, a doctor. New methods may be considerably important for a patient (if the therapy was successful), for a doctor (he has a new possible treatment where there was none before), less considerable for the entire population of patients. However, they may also lead to a change in the conception of the entire field. For instance, 10 – 20% of patients with stroke benefit from thrombolysis, still it changed neurology into an acute speciality with specialized intensive care. Similarly, neurostimulating methods, developing since 1940s, are only palliative, they do not cure the diseases, but they contributed to the creation of a surgical field related to neurology – functional neurosurgery.

Looking at neurology from a personal perspective, progress is rather gentle. A typical example – Parkinson’s disease. In the mid-1970s (when I started working at the neurology department in the regional hospital in Uherské Hradiště) most patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease were treated with anticholinergics. The medicaments worked well in the first years of the disease, however, from a modern point of view the patients were treated insufficiently. Naturally, there were no dyskinesias. Tragic was the look at advanced Parkinson’s disease patients – almost immobile, rigid, sweating, crude tremor shaking the entire sickbed. At the same time treatment with levodopa was introduced, yet without decarboxylase inhibitor it was badly tolerated and dosage, particularly in advanced stages, was insufficient. Embarrassment occurred, caused by no response to treatment in some patients, which was probably related to a fact that distinguishing between Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders manifesting with parkinsonian symptoms (Parkinson plus) were only at their beginning. However, parkinsonian syndrome was well known in psychiatric patients treated with neuroleptics, at that time almost all patients of psychiatric hospitals suffered from this syndrome. I have no memories of somebody specializing in Parkinson’s disease in Czechoslovakia.

The situation worldwide changed in the mid-1980s when the international Movement Disorders Society (today the International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society) was founded and centres specializing in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders were founded. At this time also the working group on Parkinson’s disease of the WFN (today International Association of Parkinson’s disease) was already active. Inspired by Club des Mouvements Anormaux in Paris, which I used to visit during my stay there, we started organizing meetings of neurologists interested in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders – Club of abnormal movements (basal ganglia), specialized centres in Brno and Prague in 1993, and later in Olomouc and in some regional hospitals neurologists started to specialize in PD.

Introduction of strictly scientific methods into clinical research improved diagnostics and optimized therapy, therefore the situation 20 years ago was much better than it was another 20 years earlier. Basically we had all contemporary drugs. Treatment with levodopa (with decarboxylase inhibitors) was common, however, quite a lot of patients, mainly those with tremor, were treated with anticholinergics. Shortly after new long-acting drugs appeared, in the second half of 1990s, several new modifications of known medicaments were introduced. Bromocriptine was known from early 1970s, however, a real boom of agonists of dopamine receptors came later when non-ergot agonists were developed. The change in paradigm with impact on large groups of patients was preferring modern dopaminergic agonists to levodopa, with perspective of decreased late complication of the treatment, mainly dyskinesias.

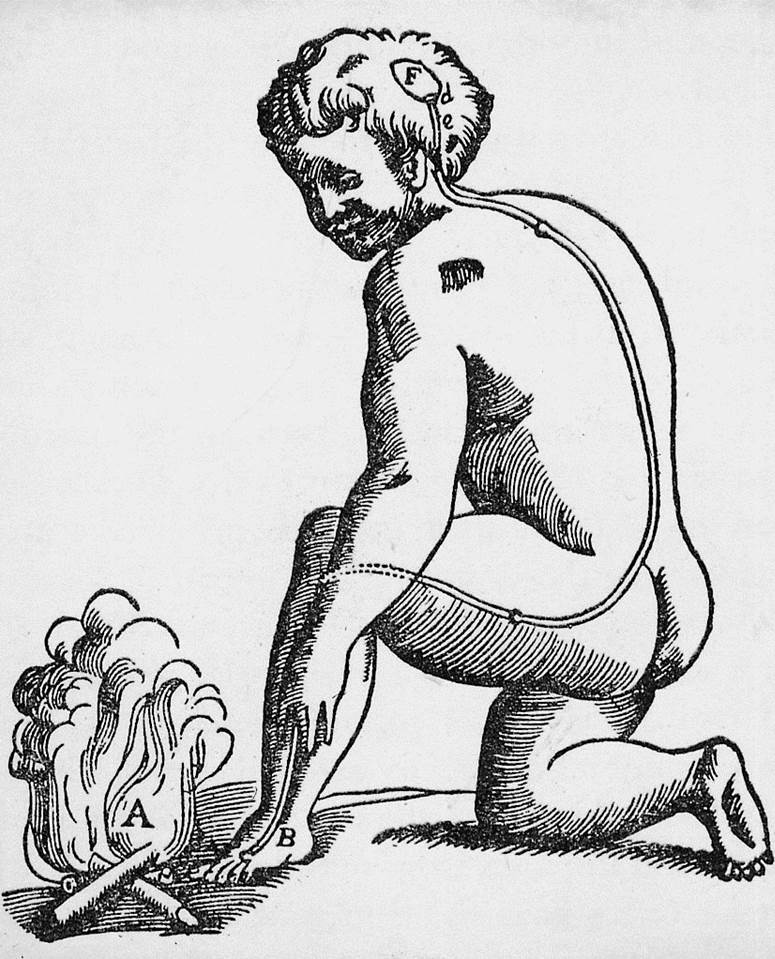

Treatment with selegiline (deprenyl, monoamino-oxidase B inhibitor) was widespread. Unfortunately, its neuroprotective effect was not proven and therefore nowadays it is rarely used, despite the fact that in early stages it is effective and well tolerated. Often the treatment was started with oral amantadine, at that time its infusion was introduced, combined with decrease of other treatment. The first COMT (catechol-orto-methyl-transferase) inhibitor tolcapone appeared, it was then temporarily called back and thus this therapy was developed only later. In 1990s subcutaneous apomorphine infusions was introduced, and in France the first modern deep brain stimulations were initiated. Its introduction resembles the term revolution (an even greater revolution was the introduction of levodopa fifty years ago). In the following decade new drug forms appeared – patches and intrajejunal infusion of levodopa.

To sum it up, in the past forty years no revolutions happened. New methods have significance only for small groups of patients, however, the entire field is changing. Many patients feel better. So do many doctors who are now more and more specialized and able to do more for their patients. It does not necessarily has to be revolution, also evolution helps. It is a general truth that evolution is sometimes more useful than revolution. Mainly because of the fact that revolution, unlike evolution, is in medicine extremely rare.

Prof. Dr. Ivan Rektor, CSc is Professor of neurology at Masaryk University, head of Neuroscience centre of the CEITEC (Central European Institute of Technology) and former head of neurology department of Masaryk University School of Medicine in Ste Anne Teaching Hospital in Brno, Czech Republic