Neurology in Germany III – The years 1933-1945 and their aftermath

Neurology in Germany III – The years 1933-1945 and their aftermath

by Helmuth Steinmetz

Following a “golden century” that had started with Moritz Heinrich Romberg in 1832 (see the previous chapters of this series) German neurology entered its dark age in 1933. Legislation implemented by the “Nazi“ party banned many Jewish fellow citizens including physicians from their professions and from using their possessions. One third of the German physicians were Jewish. This led to the turnout of many, if not the most of the nationally and internationally renowned German neurologists (as well as other physicians, scientists, artists, etc., see list below). But this was not the only devastating consequence of a radically racial and “eugenic” policy in Germany between 1933 and 1945 that remained unopposed by a silent majority – and also put medicine on a “slippery slope”. As a prelude to what followed, many university chairs and other leading positions were filled politically, and neurology and psychiatry were “reunified” in 1935. Deeper historical analyses of the subsequent ethical collapse have been and are still being conducted also by today’s German neurological and psychiatric societies.

The “Euthanasia” Programme

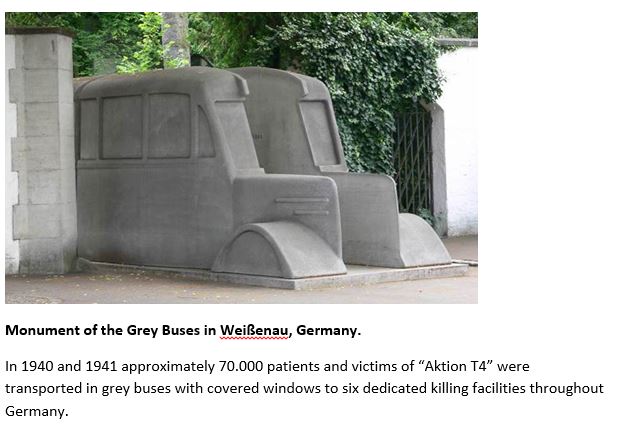

Simultaneously with the beginning of World War II, Adolf Hitler personally initiated the planning and organisation of systematic killings of chronically hospitalised neuropsychiatric patients. Children and adults living in mental homes and suffering from “schizophrenia, epilepsy, encephalitis, idiocy, paralysis, Chorea Huntington, senile dementia or other final neurological states, able to perform mechanical work only” were registered in a semi-governmental office in Berlin. Based on these paper records, each patient was graded “+” or “-“ by three “reviewers” from a group of 40 neurologists and psychiatrists, all explicit “eugenicists” and members of the Nazi party. After the transportation of their victims to dedicated killing facilities throughout Germany, approximately 70.000 “lives unworthy of life” were extinguished between January 1940 and August 1941 in gas chambers, by starving or injections. This secret “Aktion T4” was stopped by Hitler in August 1941, partly due to leaking information and resulting public protests from church officials. However, the operation had provided core personnel and “experience” for what followed immediately thereafter, the Holocaust.

Criminal experiments in human patients

Not suprisingly, the mental framework of this grim period also lowered the ethical standards and thresholds for some neurological studies in human patients. One such example are the ”Schaltenbrand experiments” carried out in 1940/1941. Georges Schaltenbrand, chairman and professor at the Würzburg University, believed that multiple sclerosis (MS) was an infectious disorder with a long incubation period. He injected cerebrospinal fluid obtained from MS patients into the subarachnoid cisterns of up to 8 human patients living in a mental home suffering from “catatonia” or “schizophrenia”. In 1943, he stated „I thought that I could take this responsibility for such studies in humans suffering from incurable total idiocy” [1]. His experiments came to no final result because his patients were selected and killed during the aforementioned “Aktion T4” (without the participation of Schaltenbrand). As another prominent German neuroscientist of his time, Julius Hallervorden from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research in Berlin suggested brain removals to be performed within “Aktion T4”. Thereby, he received and collected hundreds of specimens which he continued to exploit even in a number of postwar publications.

Postwar reorientation

After this deep fall within only 12 years, it took another two decades for German neurology to gradually regain scientific orientation, organisation and international acceptance. This restart grew out of a relatively small number of local neurological “schools” developing in divided postwar Germany. They will be portrayed in the next chapter of this neurohistorical series.

Literature

- Peiffer J. Zur Neurologie im „Dritten Reich“ und ihren Nachwirkungen. Nervenarzt 1998;69:728-733.

- Daroff RB. Schaltenbrand and Hallervorden. [Editorial] Neurology 1994;44:201-202.

———————————————————————————

Table:

Exodus: Some of the neurologists forced out of Germany [1]

Leo Alexander (1905–1985)

Max Bielschowsky (1869–1940)

Walter Riese (1890–1976)

Ernst Grünthal (1894–1972)

Kurt Goldstein (1878–1965)

Ernst Scharrer (1905–1965)

Ludwig Guttmann (1899–1980)

Hermann Josephy (1887–?)

Alfred Hauptmann (1881–1948)

Heinrich Karplus (1905–?)

Viktor Kafka (1881–?)

Alfred Meyer (1895–1990)

Felix Plaut (1877–1940)

Hartwig Kuhlenbeck (1897–1984)

Friedrich Heinrich Lewy (1885–1950)

Joseph Gerstmann (1887–1969)

Paul Schuster (1867–1940?)

Gabriel Steinen (1883–1965)

Clemens Ernst Benda (1898–1975)

Karl Stern (1906–1975)

Franz Kramer (1878-?)

Otto Marburg (1874–1948)

Paul Schilder (1886–1940)

Adolf Wallenberg (1862–1949)

Robert Wartenberg (1887–1956)

Professor Helmuth Steinmetz works at the Center of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University Hospital/ Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany