by Raja Sawaya, S. Daouk, W. Radwan, S. Hammoud

Introduction: Occipital lobe seizures are rare. They are usually the result of occipital lobe infarcts, haemorrhages, or metastatic tumours. They usually present with complex visual hallucinations, sensory or proprioceptive dysfunction, speech derangement, visual loss, and rarely homonymous hemianopia (HH) (1-4). The symptoms are usually controlled by standard antiepileptic treatments. In rare circumstances occipital lobe seizures are idiopathic and require multiple antiepileptic drugs to be controlled. We present a case of idiopathic occipital lobe seizures where the HH did not subside until treated with high dose intravenous (IV) steroids.

Case Report:

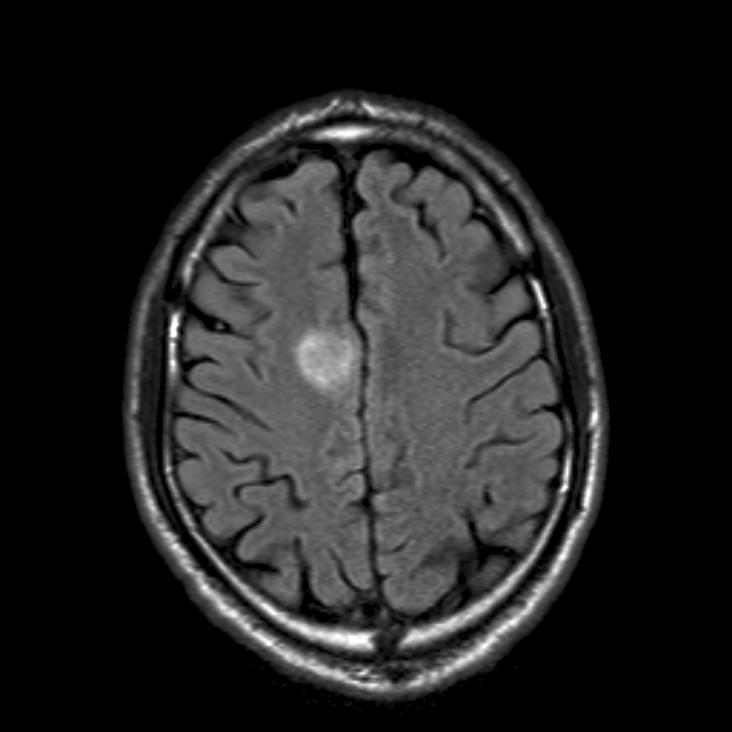

A 53-year-old man with uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia presented with few days history of episodes of complex visual hallucinations, distorted imagery, phosphenes and metamorphopsia, progressive over few days. The episodes start and subside spontaneously, lasting few minutes, and occurring several times a day. During the physical examination the patient kept having these episodes whereby he also stops speaking or responding to verbal stimulation, he rotates his head to the left, associated with left gaze preference and tonic spasm of the left arm for a few seconds. The physical examination revealed a persistant left HH irrespective of the occurrence of these episodes. The rest of the cranial nerves were normal, with normal eye movements and fundi. Speech was normal, but arrested during the visual phenomena. Cognitive functions and memory were intact. No motor weakness or sensory dysfunctions. Depressed deep tendon reflexes. No meningeal or cerebellar signs. Bilateral Babinski signs could be documented. Vital signs were normal. Basic hematologic and chemistry blood studies were normal except for a fasting blood sugar of 210mg%. MRI of the brain with gadolinium revealed cortical high FLAIR signal intensity in the right cerebral hemisphere with mild restriction on diffusion weighted images and no enhancement (figure 1). No infarcts or tumours could be seen. MRA showed patent carotid, vertebral and cerebral arteries. EEG showed a near continuous high frequency spike and sharp slow wave activity emanating from the right temporal-parieto-occipital region, which increased during hyperventilation and subsided immediately after intravenous benzodiazepine injection (figure 2). The visual hallucinations resolved with the resolution of the seizure activity, but the hemianopia persisted. Ophthalmologic examination was normal except for a complete HH confirmed by perimetry (figure 3). CSF studies revealed normal cell count, elevated protein at 1.1 g/l, normal glucose and IgG level. Negative gram stain and culture, acid fast and KOH stains, brucella and HIV, HTLV I and II serology, and negative PCR for HSV, VZV, EBV, CMV and JC viruses. CT chest, abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed no malignancies. The patient was treated with epanutin and eventually valproic acid and levitracetam were added. The visual hallucinations, head tilting, speech arrest and tonic arm spasm subsided, but the HH persisted clinically and by perimetry. Follow-up EEG showed resolution of the epileptic activity, and MRI showed marked decrease in the left parieto-occipital hyperintensity and oedema. The patient was infused with 1 gram solumedrol after which all his symptoms subsided and the HH resolved completely. The patient was discharged on tapering steroid dosages and antiepileptic therapy.

Comment by the authors

HH can be complete or incomplete and is caused by any lesion affecting the contralateral retrochiasmal visual pathway. Lesions of the optic radiation in the temporal lobe produce an incomplete HH with aphasia, complex partial seizures, memory deficits and hallucinations. Lesions of the optic radiations in the parietal lobe produce also an incomplete HH with hemineglect, sensory deficits or Grestmann’s syndrome (5). Visual field defects secondary to occipital lobe seizures have been rarely described in the literature. The defect may be quadrantic, hemianopic, or total and can occur transitory or, in very rare cases, permanently. The aetiology of the seizures can be defined, as vascular or tumoral, or can be idiopathic or cryptogenic. (1-4) The focal seizures and their manifestations usually respond to antiepileptic therapy, but the resolution of the hemianopia is variable. The hemianopia may resolve spontaneously, or upon treatment with antiepileptic therapy, or may remain permanent. (3,4)

The case we are discussing presented first with a picture of a right posterior cerebral artery infarction in a middle aged man with multiple risk factors for cerebral strokes. The stroke caused the visual disturbances and the HH. It was then complicated by occipital lobe seizures which manifested as phosphenes, metamorphopsia, visual hallucinations, tonic arm spasm, head rotation, gaze preference and speech arrest. The interesting aspects of this case and the unusual features are firstly that the diagnosis of stroke could not be confirmed by MRI or MRA of the brain and the symptoms eventually resolved without the treatment of a cerebrovascular insult. Thus the patient most probably did not have a stroke. Secondly, the HH which is part of the symptomatology of the occipital lobe seizures did not subside with the resolution of the other seizure symptoms or the epileptic activity on the EEG upon administering intravenous benozodiazepine or the antiepileptic treatment, but rather persisted throughout his hospitalization and subsided only after the first intravenous high dose steroid therapy. This suggests that the HH was the result of oedema of the temporo-pariteo-occipital region caused by the focal status epilepticus. Thirdly, there is no clear explanation why this patient developed a focal status epilepticus without any evidence for a stroke, haemorrhage, subdural hematoma, metabolic derangement, infection, malignancy, meningitis or encephalitis. The fact that the hemianopia in our patient did not resolve upon administering several antiepileptic treatments in combination, but rather after the first dose of intravenous steroid therapy suggests that its pathophysiology is inflammatory rather than a derangement in ion channel function. Thus, the treatment for the visual loss is independent of and different from the treatment of the visual abnormalities in patients with occipital lobe seizures. Furthermore, our case supports the diagnosis of idiopathic or cryptogenic occipital lobe epilepsy, as no aetiology for the seizures was found in-spite of extensive investigations. In conclusion, occipital lobe epilepsy can be cryptogenic and present with complex visual hallucinations that respond to antiepileptic treatment as well as HH secondary to cerebral oedema which should be treated by intravenous steroids to avoid permanent visual loss.

References:

1. Valli G, Zago S, Cappellari A, Bersano A. Transitory and permanent visual field defects induced by occipital lobe seizures. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1999;(5):321-5

2. Barry E, Sussman NM, Bosley TM, Harner RN. Ictal blindness and status epilepticus amauroticus. Epilepsia 1985;(6):577-84.

3. Ghosh P, Motamedi G, Osborne B, Mora C. Reversible blindness: simple partial seizures presenting as ictal and postictal hemianopsia. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 2010;30:272-5.

4. Joseph JM, Louis S. Transient ictal cortical blindness during middle age. A case report and review of the literature. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 1995;15:39-42. 5. Zhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Homonymous hemianopias, clinical-anatomic correlations in 904 cases. Neurology 2006;66:906-10.

5. Zhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Homonymous hemianopias, clinical-anatomic correlations in 904 cases. Neurology 2006;66:906-10.

Raja A. Sawaya is Professor of Neurology and Director of the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology at the American University Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon.

S. Daouk is working at the Department of Ophthalmology at the American Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon.

W. Radwan and S. Hammoud are working at the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology at the American University Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon.